“Thinking Fast And Slow” by Daniel Kahneman

Abstract

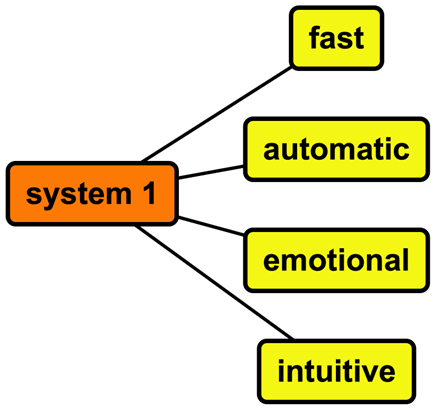

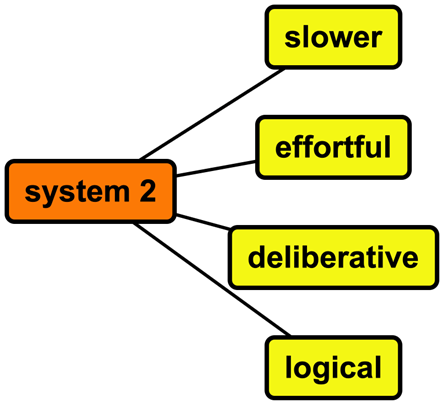

Psychological foundations of human decision-making are divided into two: “System 1” and “System 2”. System 1 is fast, automatic, intuitive, and emotional, while 2 is slower, more deliberative, logical, and effortful: Kahneman explains that these two systems often work together, but they can also conflict.

Important Points From Each Chapter

System 1:

Chapter 1 Introduces the two systems of thought that Kahneman discusses throughout the book.

2. Attention and Effort: How our attention and effort are limited resources and we use them to process information and make decisions. To do that we rely on heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to make quick decisions and how these shortcuts can lead to judgment biases and errors. Heuristics is problem solving using non-optimal methods that do not necessarily lead to correct results, but are sufficient for reaching a likely conclusion.

3. The Lazy Controller: Our brains are “lazy” so often rely on System 1 effort. To do this we tend to rely on our memory and prior experiences and that can result in these biases and errors.

System 2:

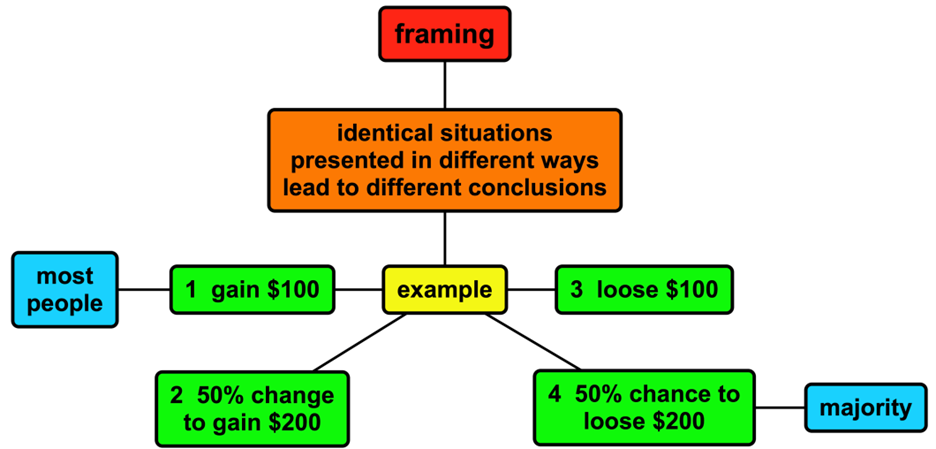

4. The Associative Machine: Our brains process and store information through associations and which can affect our judgments and decisions. We use framing to make sense of the environment. However this can lead to different judgments and decisions depending on the way the information is presented.

5. The Rules of Influence: Judgment and decision-making can be influenced by outside factors, such as emotions, social norms, and other people, affecting ability to make rational decisions. If we are aware of this we can try to mitigate the impact of framing.

6. The Psychology of Reasoning: Use of reasoning and logic also can be influenced by biases and errors, we can try to overcome these biases and improve our reasoning skills.

7. The Outside View: When making decisions, this means looking at decisions from the perspective of someone who doesn’t have all the information and considering the statistical likelihood of different outcomes.

8. Choices: Our choices can be influenced by the availability heuristic, the sunk cost fallacy, loss aversion, our preferences and values. Better decisions often can be made by considering long-term consequences.

Summary Some Concepts Introduced

Framing

Presentation of a problem or situation influences how it is perceived and decisions made about it. Identical situations presented in different ways (eg as a gain or a loss) can lead to different choices.

example

Options

A sure gain of $100

B 50% chance to gain $200 and a 50% chance to gain nothing.

Bias to choose A from A and B, as it presents a guaranteed gain.

When the options were presented differently …..

C sure loss of $100

D 50% chance to lose nothing and a 50% chance to lose $200

Bias towards D even though it is the same as B because of the second one is framed as a loss.

The book also explains (though not necessarily in the same section) this type of decision can be further influenced by other factors. For instance, if losing $200 sends a person into such complete poverty that they will not be able to eat, but losing only $100 does not, then C might indeed be the best choice. Conversely, a wealthy person with money to play with has more incentive to choose D.

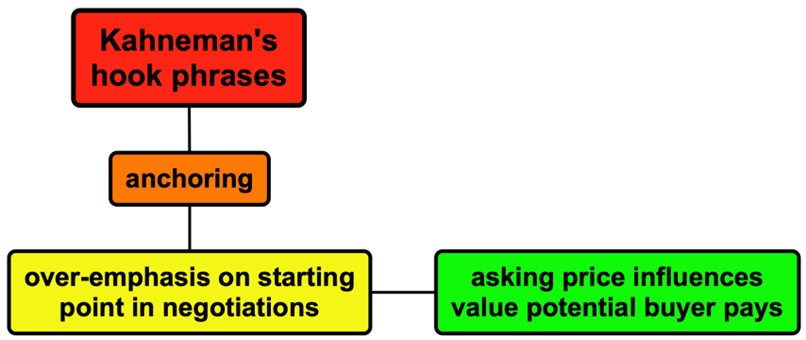

Anchoring and Adjustment

Over-reliance on the first piece of information received and failing to make insufficient adjustments from that “anchor”. Mental shortcuts when probability of an event is judged based on similarity to a typical or representative example, but what is considered “typical’ based on limited information is really not “representative”.

example

Negotiations influenced by starting price (the anchor) even if that beginning is not a reasonable one.

The Availability Heuristic

Judgments based on ease with which examples or instances come to mind but relying on readily available, rather than seeking more accurate or relevant, information. In short, basing event probability on how easily examples come to mind.

example

Lots of overlapping news stories about relatively few shark attacks, causes people to overestimate their occurrence

The Representativeness Heuristic

Probability judgements based on how similar it is to a typical or representative example, often leading to biases from failure to assess relevant contextual information.

example

Subjects where shown a list of words that include “doctor,” “lawyer,” “plumber,” and “carpenter,” then asked to pick one most likely to be followed by “guitar”.

More likely to choose “doctor” because it seems more representative of a profession that might play guitar in their spare time, even though the actual probability of any of these words being followed by “guitar” is the same.

I think this is not purely a representative heuristic, because the question framing implies one of the words is more likely to be followed by “guitar”.

Loss Aversion

People to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains; they often are

more motivated by fear of losing than prospect of gaining something of equal value.

example

win $100 or lose $50

People are likely to avoid the gamble, even though the expected value (the average outcome if the gamble were played many times) is positive because the fear of losing the $50 outweighs the potential gain of $100.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

To continue investing time, money, or other resources even when it is no longer in their best interests to do so; they feel that they have already invested too much to stop. In other words, irrational decision-making: emphasizing sunk costs (cannot be recovered) over potential benefits or losses of alternative courses of action.

example

Someone buys a book which is not worth reading. However, they read until the end because they have already “wasted” the money on it, even though they many better books to read.

Prospect Theory

Decisions in uncertain situations based on ways potential losses and gains are assessed, often being more sensitive to potential losses than gains.

example

Taking a safe, but lower paying job, because the prospect of losing a lot of money in a risky but much more lucrative venture is too unsettling.

Conclusion: What Do I Think?

The book is worth reading, it was thought-provoking. However, I do not agree that there are two distinct systems. Instead, I believe that all learning is based on emotions using the thoughts that originally are based in what Kahneman calls “system 1” that evolve into system 2 as we refine our learning.

What about math problems where there is often a clear correct answer: are emotions involved in getting to it? In learning math we learn steps by picturing their consequences: framing. Early in learning development we make mistakes doing this, but learn to avoid them as system 1 appears more like system 2. Where we choose to start is not always optimal (anchoring). Then in solving more difficult problems we put the steps together to reach an answer. However, we base the choice and sequence of steps on representation and availability heuristics. Along the way we may make false starts but are reluctant to begin again (loss aversion and prospect theory).

As we get better at this solving some math problems evolves into what appears to be system 1 (effortless and intuitive), but we went through system 2 to get there. Therefore, I do not believe there are naturally systems 1 and 2. All decision making proceeds via “system 1” until it seems like a product of “system 2” to someone who has not had that learning experience.